Never spend too long creating a game

“For Crossy Road, we made it in 12 weeks, but we actually set out to make it in six,” says Sum. “That all meant that, if it didn’t go well, we hadn’t wasted all that much time. You just don’t know what’s going to happen on mobile. If you take six months to make a game, everything might have changed by the time it comes out.”

Finding a team that gels

“Every member of the team has their own skills that complement each other,” Sum is keen to note. “Matt Ditton handles a lot of the business side, but he’s a technical programmer too. Whereas Ben is really technically awesome and led the development of Shooty Skies.”

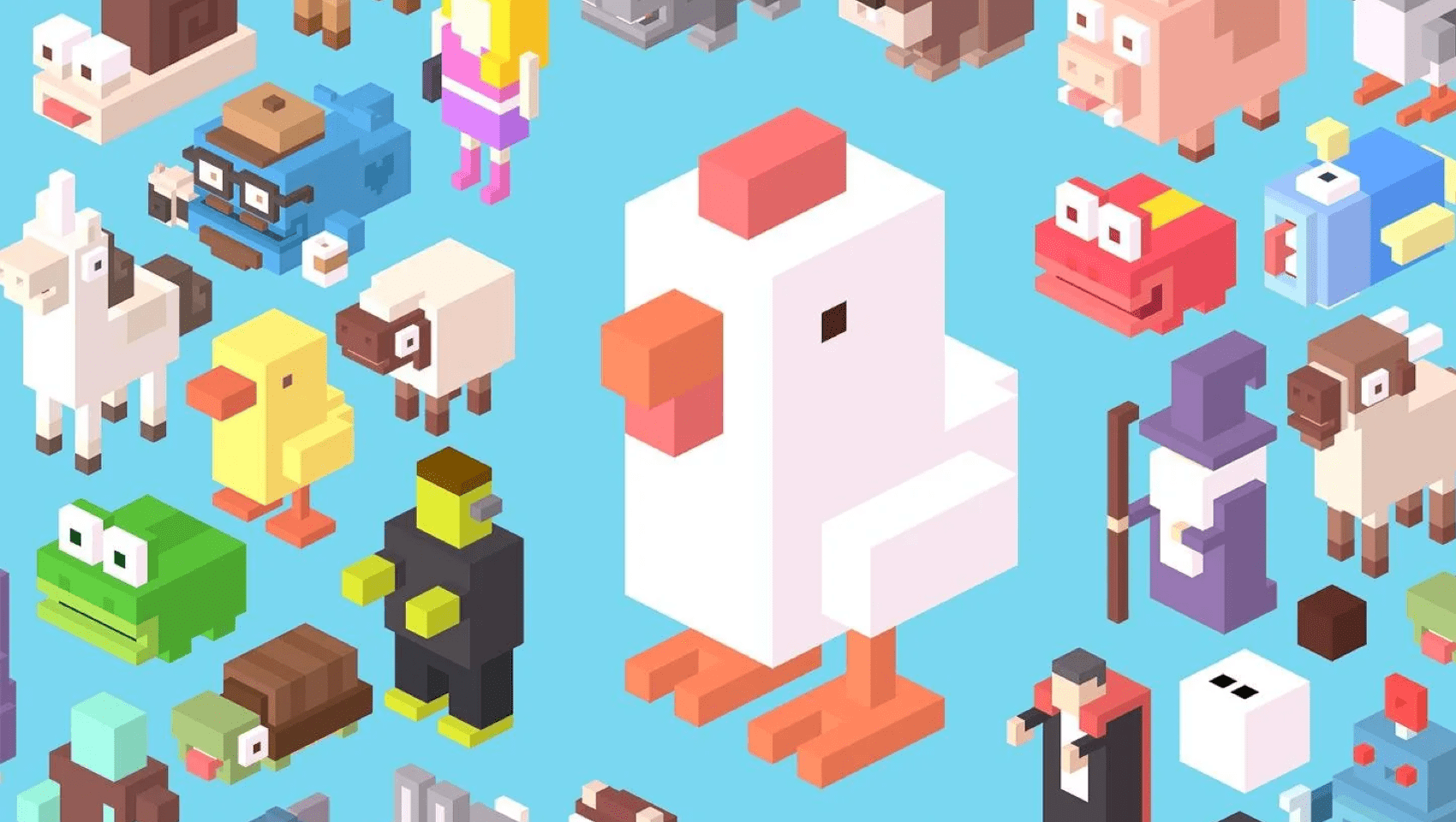

Even though they now have a bigger team, Sum said his goal was to create “something similar” to Crossy Road where they could “experiment with monetization” and where the team could put into practice the lessons they learned with the original Hipster Whale hit.

By finding a team that worked well together, it seems they were able to focus on the same goals and develop games that everybody was happy with. Which leads us to the next piece of advice.

Share a common goal

“We thought Crossy Road was a good game, but you never know what’s going to happen when a game actually comes out,” said Sum. “We concentrated on making a game that people would want to share with each other, make something funny that people would share, giving people a reason to come back the next day.”

“In general we like to make our games as inclusive as possible. Matt Hall has a technique where he pitches a game for one person, whereas I try and make them as fun as possible for me to play. The key though was that we didn’t put anything into the game that would exclude people. Shooty Skies is a bit more hardcore, but both games are very bright and accessible colors, they look inviting.”

Experiment early and often

Both Crossy Road and Shooty Skies are plugged into the GameAnalytics network, so what have Hipster Whale and Mighty Games taken from the data pooled from both releases?

“GameAnalytics has been really, really good for both games, one of the main things we used it for is gameplay design choices – looking at how long people were playing for, where they were getting stuck, bosses or enemies that are too difficult…that kind of thing.”

“With Crossy Road, I did a lot of experimentation with GameAnalytics early on, adding more and more events to answer the questions I’d had throughout development,” continued Sum. “Whenever I wanted to know the answer to a question I’d just use GameAnalytics to add an event to find out. Like, where in play were people making their first purchase? Did the banner at the end of levels have any effect? That kind of thing. It meant that, when it came to Shooty Skies, I knew what kind of events I wanted to look out for.”

Indeed, Sum’s approach mirrors that of scores of GameAnalytics developers – using data pulled from one game to directly influence (and hopefully improve) the structure and design both behind the game in question, and any follow-ups.

Keep at it

“It sounds obvious, but when people ask for advice I just tell them to make games,” Sum concludes. “It’s the biggest factor for me – you just get better by making more and more games. Going to university has definitely given me formal experience with programming, but I’d say the biggest factor is analyzing games, and you only get that by making and playing games. If you want to be a game developer, just make a lot of games, and never spend too long on them. Try and spend as short a time as possible on them, because this is a market that moves quickly and is utterly unpredictable. If you’re able to make games quickly, you’ve got a chance.”